It was 7 in the morning, and I was climbing into a Grab from the Kuala Lumpur International Airport into the city center.

As soon as I said hello, the driver, a genial Chinese-uncle-type with a thick accent and friendly smile, hit me with the usual questions: “Where you from? You speak Chinese?” Once we had established that I’m Chinese-American, and yes, I spoke Mandarin, we settled into a friendly banter which ended with the following exhortation: “If you like to eat, you must go to Jalan Alor–the Chinese eating street. I’ve lived here all my life, and I could still eat there all day long.”

That was the first time I heard that recommendation, but it wasn’t the last–pretty much every local I spoke to raved about Jalan Alor. When dinnertime finally arrived and the street came to life, I understood. (Whether it’s fair to call it a Chinese eating street is up for debate, but Chinese food is certainly well represented.) Sticky chicken wings, crimson curry mee, and creamy coconut ice cream vied for attention, each one delicious in its own right. But next time, I’ll be making a beeline for one stall: Restoran Meng Kee Grill Fish, home of Jalan Alor’s most famous oh chien, or oyster omelette. My personal favorite of the many versions of the Hokkien oyster omelette (see the Story section of the recipe for more details on this diaspora dish!), the combination of eggs, starch-based batter, and fresh oysters produces fascinating textural contrast. Crispy yet gooey, slick yet creamy, it’s the sort of dish that far exceeds the sum of its ingredients.

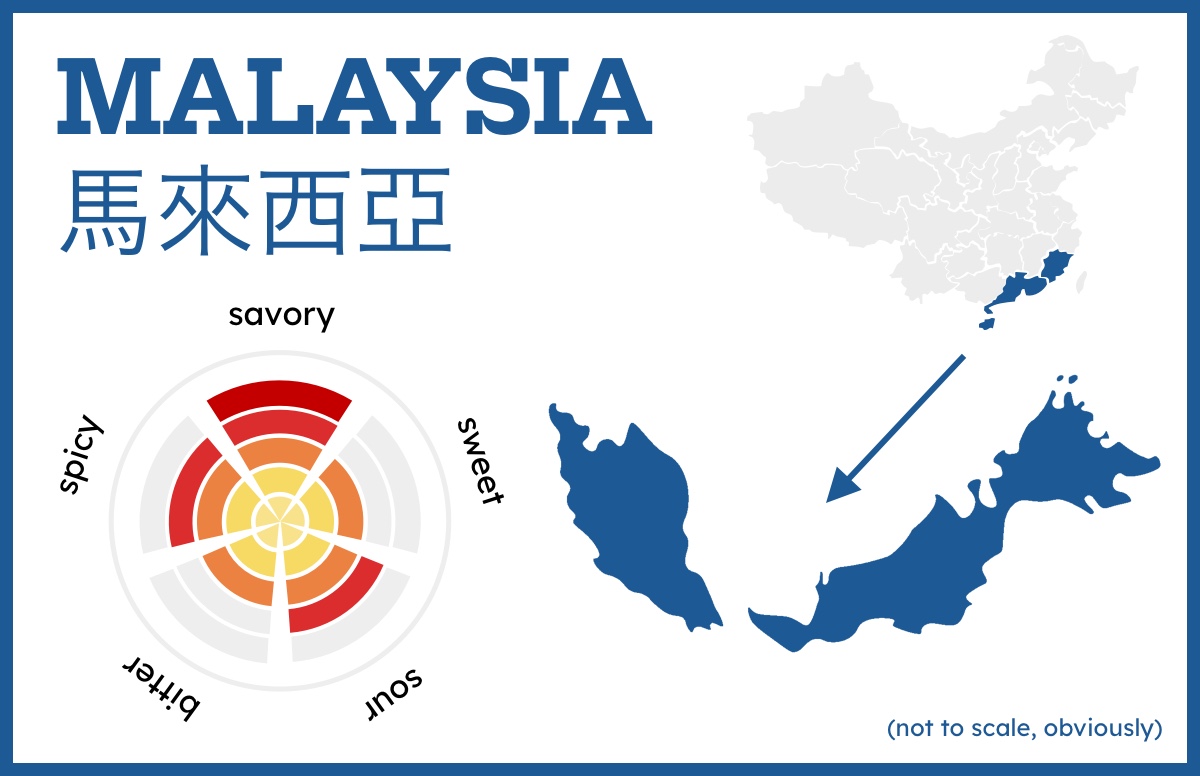

As you can tell by now, the theme of this issue is Malaysian Chinese food. Due to centuries of immigration from Southern China, many of Malaysia’s most iconic dishes have recognizable relatives in Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan, but were transformed by their time in the tropics*. Think noodle soup laced with chilies and tamed with coconut milk; chicken rice nestled in pandan’s fragrant embrace; and, of course, oyster omelettes enlivened with a touch of fiery sambal. If your exposure to Chinese cuisine is mostly through Southern Chinese food, as mine was, the results are an uncanny valley of flavor, in the best of ways.

But of course, we can’t discuss Malaysian-Chinese food without some discussion of Peranakan** / Baba Nyonya cuisine. Some 500 years ago, a large wave of Chinese immigrants arrived in the Malay Peninsula, and married local women. The descendants of these intermarriages are known as Peranakans or Baba Nyonya, and their food features a blend of Chinese ingredients, Malay spices and techniques, and colonial-era European influences whose spicy, sour, and tangy flavors would be unfamiliar to most Southern Chinese. A great example is assam laksa, a delightfully tangy rice noodle soup made with fish broth and tamarind (the word asam means “sour” in Malay, referencing the tang of the tamarind fruit). It’s a truly unique culture and cuisine that is struggling to survive the test of increasing globalization, which is all the more reason to explore and eat it while you still can!

*Tracing the origin of a food is always a challenge, and that is perhaps especially true when it comes to diaspora cuisine. Variants of these dishes can be found throughout Southeast Asia, and which version is the "real" or best one is often highly contested.

**While it's most often used to refer to Peranakan Chinese, the term "Peranakan" can also refer to other immigrant communities in the region, such as the Chitty and Kristang.

The Recipes

Oh Chien (Oyster Omelette) • 蚵仔煎

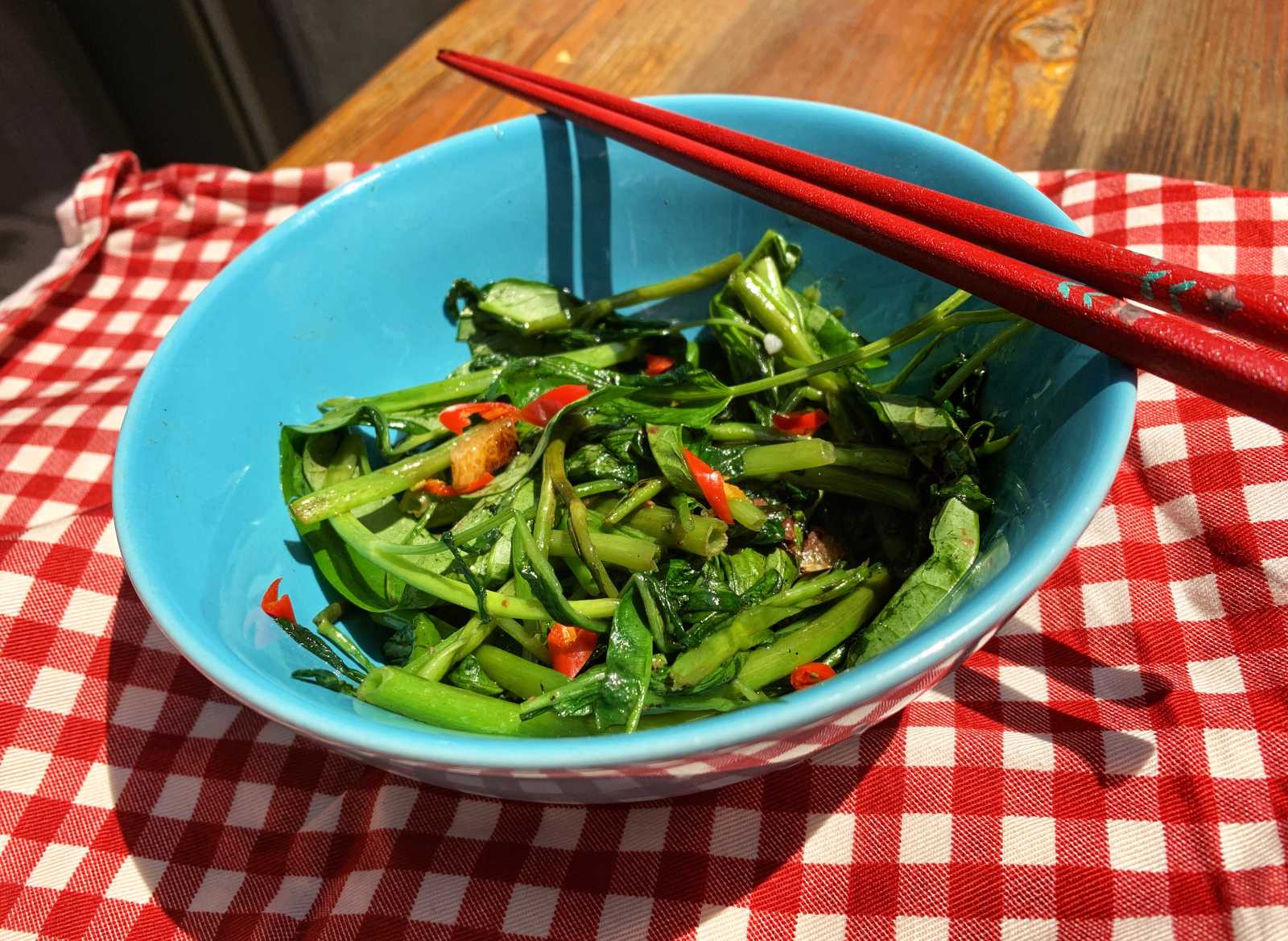

Stir-Fried Water Spinach with Shrimp Paste • 空心菜炒虾酱

This issue’s menu features the abovementioned oyster omelette and a vegetable stir-fry loosely inspired by kangkung belacan, the Malay name for stir-fried water spinach with shrimp paste. If you’ve read this far and the thoughts running through your head are along the lines of the following: Oh no–I can’t find/can’t afford/just plain don’t like oysters! Uh oh… I’m no good with spicy food. I don’t know what any of this stuff is, but it sounds scary. Never fear–the recipes I’m sharing today are highly substitutable. They also don’t rely on spice for flavor, so it’s totally fine to omit the chilies/sambal should you not be on Team Spicy. Check out the Tips sections of the recipes for more subsitutes! Try the real deal: If you’ve read this far and are dreaming of trying the real-deal Malaysian oyster omelette, it might not take a trip to Kuala Lumpur. The first oyster omelette to capture my heart was the Oh Chien at Kopitiam, a Malaysian fast-casual joint in New York City's Chinatown (it appears they’re doing delivery via Caviar, if you’re in the area but still quarantined).

Plan of Attack

Thanks for all the positive feedback on last issue’s Plan of Attack! We’re back at it again (you’ll notice that it’s not so different from last week–soon enough, it’ll be second nature!):

Equipment: Wok or large frying pan

Cook rice using your method of choice (I prefer an Instant Pot or rice cooker).

Set the table: These dishes are quick to cook, so save yourself a last-minute rush by setting out a rice bowl and chopsticks for each diner.

Mise-en-place: Prep all the ingredients, separating by recipe. Ready a medium bowl or plate for the water spinach and a serving plate for the oyster omelette (choose one at least as large as your frying pan, or you can serve directly out of the pan, as I did.)

Cook the water spinach and transfer to the serving bowl or plate. Cover with a lid or plastic wrap to keep warm while you cook the omelette, if desired.

Cook the omelette and transfer to the serving plate, if desired.

Serve the dishes family-style with plenty of steamed rice.

Food for Thought

Culinary Diplomacy

The concept of culinary diplomacy, or gastrodiplomacy, holds that “the easiest way to win hearts and minds is through the stomach". Perhaps the most famous instance was through Global Thai, a Thai government program that aimed to establish at least 3,000 Thai restaurants around the world through pre-fab menus, loans, training, and more. The result was a smashing success–today, there are over 5,000 Thai restaurants in the US alone. Meanwhile, words like Pad Thai and green curry have entered everyday vernacular. That said, I’ve long been of the opinion that Chinese cuisine could use some gastrodiplomacy, too. Though Chinese food is popular abroad, it suffers from a number of issues that other cuisines do not. One in particular that I’ve long lamented is naming. The Pinyin romanization system doesn’t lend itself to natural pronunciation in English, so dishes that have a widely-recognized name in Chinese are often translated in a variety of ways. This makes it difficult for non-Chinese speakers to know what dish they’re eating, even if they like it. (Compare that to Japanese cuisine–rather than saying “sliced raw fish on rice,” we simply say “sushi.”)

This dish, kou shui ji / 口水鸡, literally translates to "saliva chicken," but is also known as "mouthwatering chicken" (closer to the intention, and my preference) or simply "steamed chicken."

There are a few exceptions, such as mapo tofu (mapo doufu / 麻婆豆腐 in Mandarin), but more often than not we end up with high-level translations, like “soup dumplings” in place of xiao long bao (小笼包). If the Chinese characters for the dish’s name aren’t included on the menu, it can be hard even for a fluent Chinese speaker to know what he or she is ordering. Would it be better to always stick with the pinyin version? The hurdle of pronunciation makes me venture to say no, but that’s the reason I make an effort to always include the Chinese names of dishes in my recipes, too. If you’re reading this and have other ideas, I’d love to hear them!

That's all for now! I hope enjoyed learning about a cuisine from the wider Chinese diaspora. That said, I vastly underestimated the time all the writing, photography, and illustration takes, so I'll be shifting to a monthly cadence starting next issue. Thanks for bearing with me, and I hope you look forward to the June issue! 🙏 In the meantime, your questions, comments, and feedback are always welcome. Simply reply to this email or leave a comment on the webpage or Instagram!