It’s a chilly night in Tokyo, and I’m walking down one of the city’s countless spindly back streets.

It’s cold enough that I can see wisps of breath dissolving beyond my mask. In front of a brightly lit storefront, a paper lantern attracts hungry diners with brightly emblazoned characters: ラーメン, or ramen. To my left, my companion for the night's stroll turns to me and asks: 中華はどう? How about some Chinese food?

It’s true! Here in Japan, ramen is one of the staples of Chinese cuisine. In fact, an alternative name for the dish is 中華そば: chūka soba, or literally, “Chinese noodles.” (This is why, to the confusion of many a foreign tourist, the famed Michelin-star ramen restaurant Tsuta calls itself a "Japanese soba noodle" shop.) Nowadays, ramen is the more common name, derived from the Chinese 拉麵 — la mian, literally “pulled noodles.” As such, it is usually written in katakana, the Japanese script used for borrowed words.

Although ramen has gained quite the cult following abroad, it's far from the only star of the Chinese-Japanese restaurant menu. Other favorites include エビチリ ebi chili (stir-fried sweet chili shrimp), 油淋鶏 yuurinji (fried chicken in a sweet, vinegary soy sauce), and the star of this week’s menu: 坦々麺 tan tan men, a soupier, milder take on the famous Chinese dish 担担面 dan dan mian.

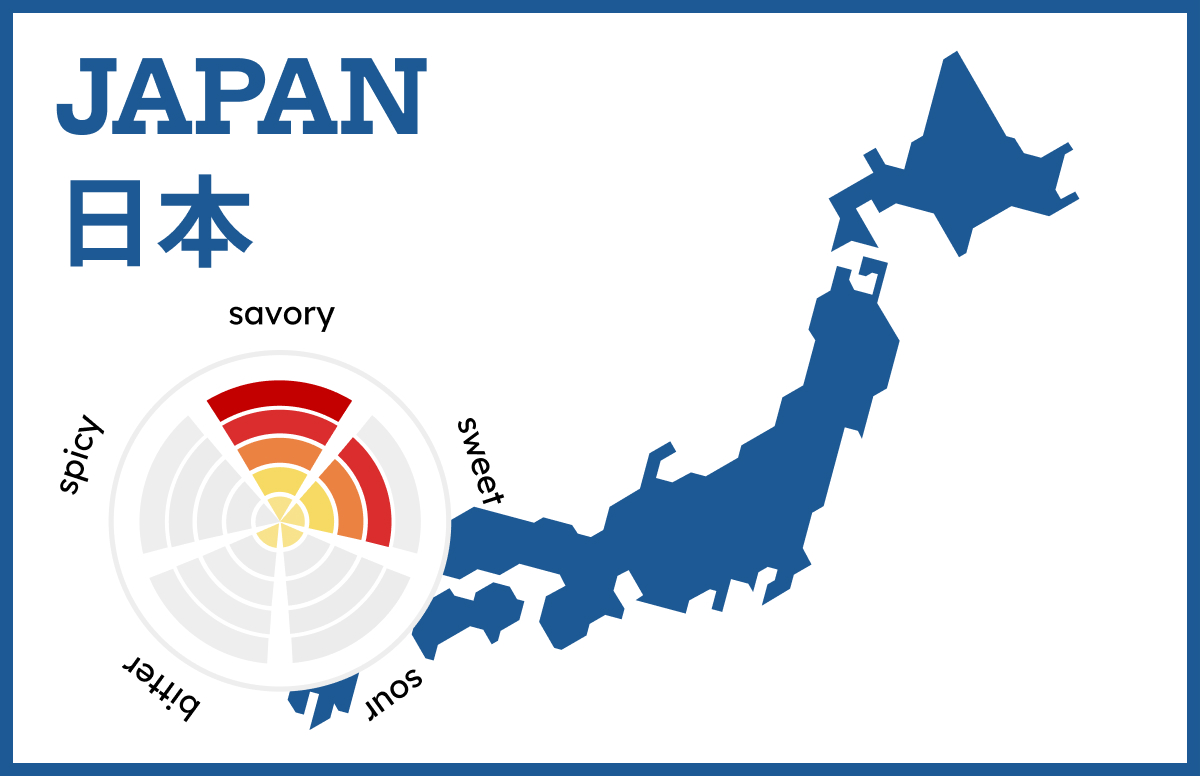

Many of these dishes draw inspiration from Sichuanese cuisine. As such, the popular image of Chinese food in Japan is of spice—both 麻 ma, the tingly sensation of Sichuan peppercorns, and 辣 la, the searing heat of chili peppers. This image is so pervasive that many of my Japanese friends were surprised to learn that entire regions of China are devoid of spicy foods. Despite this association, Japanese-Chinese dishes are usually much less spicy than their Chinese counterparts. Having been adapted to local tastes, they tend towards the saucy, sweet, and vinegary.

Though fine dining establishments featuring shark fin’s soup and Peking Duck aren't uncommon, it’s likely comfort foods like tan tan men that have made Japanese-Chinese food incredibly popular here in Japan. Since moving here, I was surprised at the number of folks I've met who, when prompted to name their favorite cuisine, will proudly proclaim "chūka"!

(I'm inclined to agree.)

The Recipes

Soymilk Tan Tan Men • 豆奶担担面・豆乳坦々麺

Smashed Cucumber Salad • 拍黄瓜・叩きキューリ

When I arrived in Tokyo from New York City (home to 2.5-hour queues for ramen joints such as Ippudo), one of many surprises was the lack of glamor associated with ramen. There’s no doubt that ramen is both very well-loved and very Japanese; from the southern city of Fukuoka, known for its milky-white pork bone soup and thin noodles, to the northern city of Sapporo, where rich miso ramen arrives adorned with local corn, it seems as if every major city takes pride in its ramen. That said, to the average Tokyo-ite, the idea of queueing up for a $20 bowl of ramen is shocking. As a colleague of mine put it, “I never understood why foreigners are so crazy about ramen. It tastes good, but it mainly makes me think of cheap meals after drinking too much in college.”

I'm generally aligned with that statement. Despite living in Tokyo, I can count the number of times I’ve eaten ramen in the last year on one hand—there are simply too many other things I'd rather eat. This soymilk tan tan men is one of the exceptions. Unlike authentic Sichuanese dan dan mian, which features fierce spice and funk, tan tan men trades heat for savory miso and sesame. Add in soymilk—inspired by ごま豆乳鍋 goma tonyu nabe, a sesame-soymilk hotpot popular here in the winter—and you have a rich, slightly sweet, super-comforting bowl of noodle soup. To balance out all that richness, I like to serve tan tan men with 叩ききゅうりtataki kyūri, a cooling cucumber salad in a soy-vinegar sauce.

Plan of Attack

Equipment: Saucepan, wok or saute pan

Set the table: Prepare a noodle bowl, small plate, Chinese soup spoon, and chopsticks for each diner.

Mise-en-place: Prep all the ingredients for the tan tan men separately.

Smash and salt the cucumbers and set them in the fridge to drain. Prepare the cucumber sauce as well, but save it for the end.

Prepare the tan tan men soup and keep it warm on the stove.

Finish the cucumber salad: Drain the cucumber juice and pat dry. Pour over the sauce, toss, and add garnishes.

Cook the noodles and ladle into bowls, followed by enough soup for each diner.

Enjoy piping-hot, and don’t forget to slurp!

Food for Thought

Bunovation

A sale on bao at the FamilyMart next to my office in Omotesando.

When I was a kid, I actually wasn’t a fan of most Chinese food. One exception, however, is the venerable Chinese steamed bun, or 包子 bao zi. These fluffy, yeast-leavened buns come stuffed with various fillings, such as bright-red BBQ pork, red bean paste, and salted egg (a true delight if you enjoy the combination of salty and sweet!)

I'd say that I'm pretty well-acquainted with the world of bao. When I was a tiny kid, the promise of a freshly-steamed bao made the many long car rides to Manhattan Chinatown worthwhile. And when I interned in Beijing, most of my morning commutes involved a quick stop at a roadside cart for a piping-hot bun.

The first time I visited Japan, I was pleasantly surprised when I walked into my local FamilyMart (a popular convenience store brand here) and was greeted by a case of beautiful steamed buns. Though I couldn’t read Japanese at the time, my eyes were instantly drawn to the image of a bun with a bright yellow exterior and red-and-white filling. Could it be some kind of curry bun? Perhaps salted egg?

When I took a bite, I was shocked to discover that it was a ピザまん pizza man. That's exactly what it sounds like: a typical Chinese steamed bun, but stuffed with tomato sauce and melty cheese. Soon, I discovered that while pizza buns are a beloved staple, Japanese convenience stores are actually hubs of steamed bun innovation. Since then, I’ve been delighted to try seasonal flavors including kalbi, garlic shrimp, chashu-and-runny-egg, mapo tofu, cajun chicken, hujiaobing, and lamb hotpot (my personal favorite!), to name a few. What will they come up with next? I can't wait to see. (If lamb bao sounds good to you, check out my recipe for Pan-Fried Cumin Lamb Buns!)

As always, thanks for reading! I hope you'll be pleasantly surprised by how easy it is to whip up some some soul-food noodles at home. Speaking of warming foods, I'm currently spending my winter break at home working on a few more recipes perfect for cold-weather cooking. Hopefully, I'll be able to share them with you in an issue in early 2021. 'Til then, happy holidays!