The wafting aroma of cumin. Stern-faced hawkers in white taqiyahs. Iridescent fountains of pomegranate juice. If it weren’t for the raucous backdrop of Mandarin conversation, you might have convinced me that we were in Turkey. But no – this is Xi’an (西安), the capital of China for ten imperial dynasties. Even if you think you don’t know anything about Xi’an, you’ve probably heard of its most famous artifact: the Terracotta Warriors. Awe-inspiring in number and painstaking in detail, Qin Shi Huang’s ceramic army is no tourist trap. I still remember being shocked into silence when I first set eyes upon it at age eight, a feeling that remained unchanged at twenty-six. And yet, my real reason for traveling to Shaanxi (陕西)–the Northwestern province of which Xi’an is the capital–was not clay soldiers, but the food. Sandwiched between spice-loving Sichuan (四川) and salt-forward Shanxi (山西), Shaanxi embraces both and adds an additional layer: The bounty of the Silk Road. Xi’an is home to many Chinese minorities, including a significant number of Hui Muslims (回族): Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. Over time, their cuisine has become an essential part of the local food culture. Think cumin and coriander, persimmons and yogurt, all beautifully interwoven with Han Chinese ingredients and cooking methods.

But that’s not the only differentiating factor of Shaanxi cuisine. Though Southerners might declare that “It’s not a meal if it doesn’t have rice!”, the people of Xi’an beg to differ. Here in the Northwest, the arid, cold climate is a poor fit for rice production, which means wheat reigns supreme. If you ask me, it's not much of a loss – after trying the springy noodles, crispy flatbreads, and chewy dumplings that symbolize this region, I’d happily trade in my bowl of rice. In fact, I sometimes joke that my love of these foods is genetic: My maternal grandfather is ethnically Hui, and his father was the Imam of a mosque in Hong Kong, so he kept strictly halal growing up. Though my family no longer practices Islam, I like to think that when I cook a good plate of cumin lamb, I’m paying tribute to that branch of my heritage. While we're on this topic, I'd like to mention the precarious situation currently faced by the Muslim community in Northwest China. Though it doesn't get much attention from Western media, the suppression of minority culture bears a troubling resemblance to the stateside crisis. If you haven’t heard of it before, I hope you’ll take a moment to learn about it.

The Recipes

Cumin Lamb Noodles • 孜然羊肉面

Tiger Salad • 老虎菜

This month, we’re making a weeknight-friendly bowl of noodles featuring one of those flavor combinations that was just meant to be: cumin lamb. It’s loosely inspired by both the street foods I ate in Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter and the NYC institution Xi’an Famous Foods, whose insanely flavorful hand-ripped noodles put Northwest Chinese food on the radar of many New Yorkers for the first time. There are no set toppings for the dish, so if you’re not a fan of chilies or lamb, never fear–I’ve included substitution suggestions in the Tips section of the recipe, as usual! To balance the heaviness of the noodles, this menu comes with two cooling sides: my go-to yogurt sauce, which I make almost every time I serve lamb or spicy curries, and Tiger Salad, a refreshing cilantro salad whose stripes of julienned vegetables give it its name. The latter is especially fitting for this issue, as the tiger is a symbol of the wider region. If you ever have the chance to visit Xi’an, you’ll surely spend some time on the City Wall (I recommend going for a bike ride around the perimeter!), where you’ll see a tiny metal tiger adorning each lamppost. Try the real deal: The New Yorkers among you probably already know Xi'an Famous Foods (they're doing hand-pulled noodle kits via delivery for COVID!), but if you're located in San Francisco, I recommend Terra Cotta Warrior for some authentic, delicious Xi'an eats. If you're here in Tokyo, these aren't Xi'an style, but you can try authentic Chinese Muslim foods at Silk Road Tarim in Shinjuku and Aliya Halal Restaurant in Ikebukuro–the latter's ¥100 lamb skewers are to die for!

Plan of Attack

As usual, here’s my suggested game plan for assembling this week’s meal!

Equipment: Wok or large frying pan

Set the table: You’ll need a medium-to-large noodle bowl and chopsticks for each person, plus serving utensils for the yogurt sauce and tiger salad.

Prep the yogurt sauce for the noodles and set it aside in the fridge.

Make the Tiger Salad and pop it in the fridge, too.

Mise-en-place: Prep all the ingredients for the noodle dish. Separate the aromatics, vegetables, lamb, and noodles.

Stir-fry the noodles and portion into 4 bowls.

Serve, passing the yogurt sauce and Tiger Salad around the table. Some iced tea wouldn’t hurt, either–I personally love this meal with some cold-brewed green or chrysanthemum!

Food for Thought

Suds To Be You

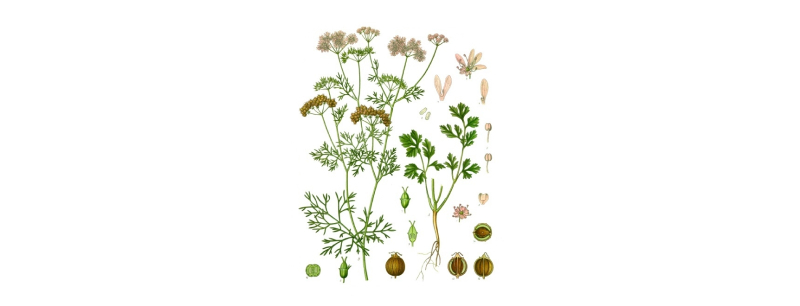

Chances are, a good portion of you cringed when you saw that the main ingredient in Tiger Salad is cilantro (or coriander, for the non-North-Americans among us). A few years back, it seemed like all of my food-nerd friends were talking about how a significant minority of the population is genetically predisposed to dislike cilantro. This minority has an olfactory-receptor gene variant called OR6A2 that makes them especially sensitive to aldehydes, which are present in both cilantro and standard household soap–thus, the dreaded "soapy taste." Soapy or not, the fervor of many cilantro-haters hasn’t stopped it from becoming a staple in many countries, including China. In fact, while the modern term “cilantro” comes from Spanish, the herb was dubbed “Chinese parsley” by New Yorkers who first encountered the herb at the farms of Chinese immigrants in Astoria in the 1890s.

In Chinese, cilantro is known as 香菜 or xiāngcài, literally “fragrant vegetable,” and is commonly used to add freshness and color to noodles, soups, and stir-fries. What’s more, the entire plant is a key ingredient in Chinese medicine, where the leaves, seeds, and roots (yes, they’re edible!) are all used for different purposes. The leaves are thought to regulate blood circulation and to warm the body, which is one reason they are often used in Chinese medicinal dishes such as hotpot. Here in Tokyo, we’re in the midst of a cilantro craze. From ramen-ya to cilantro specialty shops, the leafy herb is everywhere. It's fairly common for any “Asian” restaurant to offer it as a topping for an extra ¥50 or ¥100. (Somewhat hilariously for native English speakers, the katakana-English word アジアン, which is based on the word “Asian”, is usually used to refer to Asian countries other than Japan). As the type of person who thinks that cilantro ice cream sounds pretty good, I have no complaints!

That’s all for this month! I hope you learned something new (and didn't laugh too hard at my awkwardness in the video... we learned a lot by making it)!

I'll end this issue with two requests, if you care to humor me:

What type of content would you like to see in future issues of Journey East? Write a dish, medium, region, or anything else that comes to mind in this Google form and hit submit. I look forward to hearing what tickles your fancy!

If you know anyone who might enjoy reading about Chinese food culture, please share Journey East with them! You can suggest they check out previous issues at journeyeast.co or share a subscribe link directly.

This zine is a labor of love, and nothing would make me happier than to share that love with more people. I'll be back next month with a fresh theme from the wider Chinese diaspora. In the meantime, stay safe and healthy, take some time for yourself, and tuck into some good food!